Analysis and Verification¶

BPjs programs can be analyzed by traversing their possible runtime states. In other words, given enough time and resources, it is possible to visit each state a b-program might reach. Such traversal can be used to verify both that all states are OK (for some formal definition of “OK”) and that transitions between states conform to certain constraints. Like in any verification/formal analysis system, the “enough” part in “enough time and resources” might translate to a prohibitive amount. However, because BP looks at program states at a higher level than traditional formal analysis systems, formal analysis of non-trivial b-programs is useful and practical even on a regular laptop.

Note

Analysis is done directly on the b-program source code. No model transformation is involved in the process.

BPjs supports verification of both safety and liveness properties. As a safety example, BPjs can be used to verify that a b-program will never end up in a deadlock, or that a certain event could never be selected. As for liveness, BPjs can be used to verify that a certain event will happen eventually.

Analysis is not limited to verification — it is also possible to generate drawings of the runtime state-space, to collect statistics about the paths in its underlying graph, etc. BPjs’ modular structure allows performing such analyses by registering a listener, as explained below. We should start with some quick theory, though.

DFS over B-Program States¶

Program analysis is done by scanning all possible states a b-program can be in, and all the transitions between those states. These states and transitions form a graph, called “state space”. This is of course quite complex, as often the amount of states a program can be in is very large, or even unbounded. Some techniques for alleviating this problems exist; however, they are beyond the scope of this document.

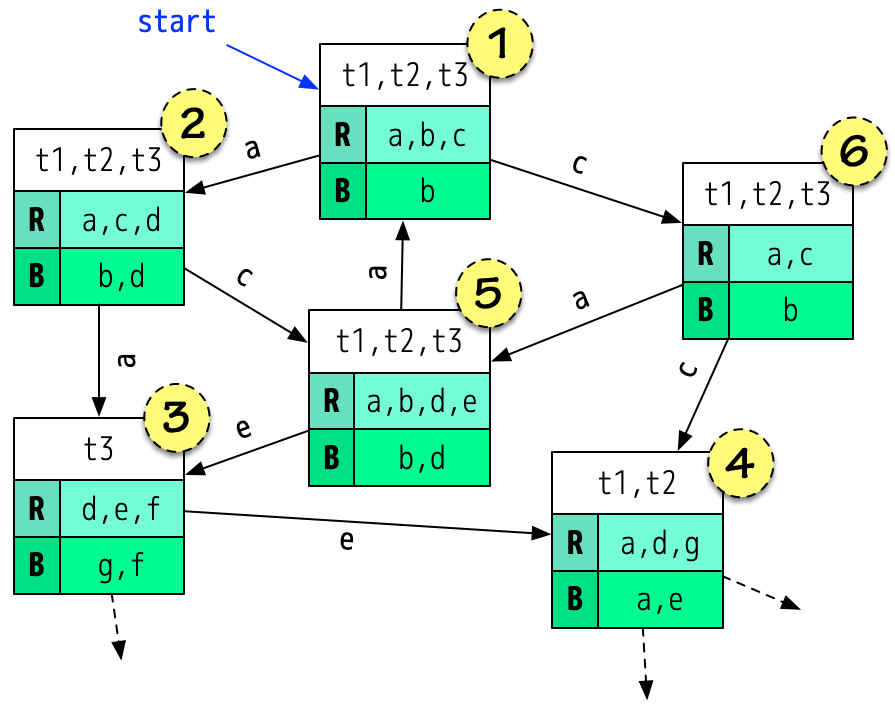

In the state space graph of a b-program, synchronization points are the vertices and events are the edges. The outgoing edges from a given vertex are the events that are requested and not blocked at the synchronization point said vertex represents. See the image below for a simple example.

A state space of a sample b-program with 3 b-threads. Synchronization points are vertices, and events that are requested and not blocked serve as edges that connect between them.

In order to traverse the state space, we use a DfsBProgramVerifier, like so:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | BProgram program = new SingleResourceBProgram("...."); // create a regular b-program

DfsBProgramVerifier vrf = new DfsBProgramVerifier(); // ... and a verifier

vrf.setProgressListener(new BriefPrintDfsVerifierListener()); // add a listener to print progress

VerificationResult res = vrf.verify(program); // this might take a while

res.isViolationFound(); // true iff a counter example was found

res.getViolation(); // an Optional<Violation>

res.getViolation().ifPresent( v -> v.getCounterExampleTrace() );

// ExecutionTrace leading to the violation.

|

The verifier performs a DFS (depth-first search) on the state space. This is of course quite a naive algorithm that can be improved on (we certainly plan to). Still, DFS works pretty well, since it finds errors that are away from the program’s starting point. Errors that are close to that point are typically found by the programmer, using the good old technique known as “read the code and understand what it does”. In case the depth of a run is unbounded, the length of the scanned path can be limited.

Classes Involved in Analysis¶

The analysis process involves a few classes of note. When writing new types of analyses, consider sub-classing some of the below, as it may save you hard work.

DfsBProgramVerifier- Orchestrates the analysis/verification process: starts the b-program, manages state traversal, runs the DFS, etc.

DfsBProgramVerifier.ProgressListener- A listener to the analysis process. Notified when a violation is found, and can decided whether analysis should continue. Also notified about “usual” lifecycle events, such as verification starting and ending.

ExecutionTraceInspection- An inspection object, which takes an execution trace, and decides whether it violates some contract. During analysis, a

DfsBProgramVerifierinstance holds a set of these. Each time a new vertex or a new loop is found, the verifier sends them to these objects for inspection. BPjs ships with multiple such inspections, as static fields in theExecutionTraceInspectionsutility class (note extrasat the end, like in other Java utility classes, such asjava.nio.file.Paths). Violation- When an

ExecutionTraceInspectioninstance finds a trace that violates some requirement, it describes that discovery using an instance of this class. VisitedStateStore- In order to detect cycles in a b-program’s execution graph, the verifier needs to know whether a given state was already visited. This is done using an instance of this class. BPjs ships with three implementations: One that looks at the entire state of the b-program, on that looks only at the hash code of that state, and one that assumes that all states are new.

Tip

The forgetful visited state store (ForgetfulVisitedStateStore) is useful for traversing all graph’s edges, since it does not stop a scan when it arrives at a node it already visited. The scan is still resilient to cycles - these are detected by looking at the DFS stack, not the visited state store.

Verifying Safety Properties¶

BPjs models are verified for most safety properties using assertions. During execution, b-threads may call bp.ASSERT(cond, message). If cond evaluates to false, the b-program is considered in violation of its requirements. This mechanism allows intuitive verification of requirements such as while flying, the doors can’t be opened:

bp.registerBThread(function(){

while ( true ) {

bp.sync({waitFor:FLYING});

bp.sync({waitFor:DOOR_OPENED, interrupt:LANDED});

bp.ASSERT(false, "Can't open the doors when flying");

}

});

Assertions can be used with any boolean expression. They can be used at runtime too, where a false assertion causes a b-program to terminate.

An interesting corner case for safety properties is deadlock detection. When in deadlock, none of the b-threads can advance. In particular, when a b-program is deadlocked, none of its b-threads can invoke a false assertion. Thus, deadlocks are detected using a specific inspector, and not using a b-thread.

Tip

message is an optional parameter explaining, in human-readable terms, what went wrong.

Verifying Liveness Properties¶

Liveness properties require that “something good will happen eventually”. In order to specify this, BPjs borrows the concept of “hot” locations from its ancestor, Live Sequence Charts (LSC). A b-thread can declare a sync as “hot”, which means that it must eventually advance beyond it. For example, a requirement such as any request must receive a response, can be verified using the following b-thread:

bp.registerBThread(function(){

while ( true ) {

var req = bp.sync({waitFor:ANY_REQUEST});

bp.hot(true).sync({waitFor:responseFor(req)});

}

});

The first bp.sync is a non-hot (“cold”) sync, which means the writer of the b-thread is fine with that b-thread being stuck there forever (for example, if requests stop arriving). The second sync, on the other hand, is marked as hot (by calling bp.hot(true) before calling sync). This means that the writer of the b-thread does not allow the b-thread to be stuck there forever; eventually, the b-thread must move beyond this synchronization point. Here, this means a response to the received request must be sent. It is possible to specify abort conditions for this requirement, by providing values for waitFor and interrupt. This is similar to regular (“cold”) synchronization points.

Types of Liveness Violations¶

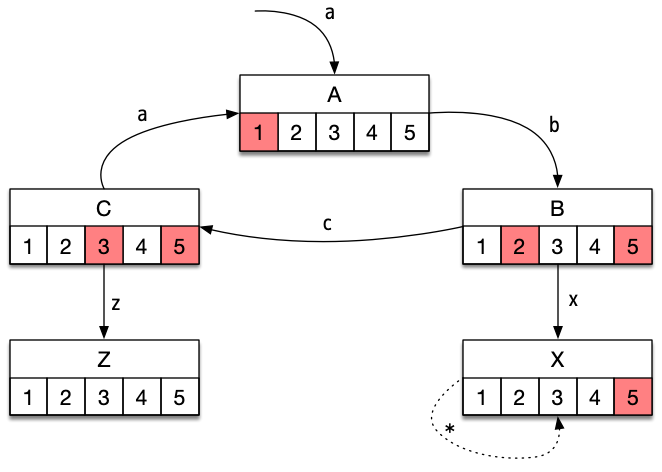

A liveness violation occurs when some set of b-thread remains hot forever. This can happen on two cases: a) there’s cycle in the b-program’s state space, where at least a single b-thread is hot at each point; or b) the program can terminate while at least one of its b-threads is hot. These violation types are described in more detail below, and in the accompanying figure.

Note

Not all hot cycles are bugs! Some systems must be able to advance infinitely. One example would be a traffic light controller, which must be able to infinitely cycle between its lights.

- Hot Run (of a group of b-threads)

- There exists a group of b-threads that can get into an infinite loop where at least one of its member b-threads is hot at each synchronization point. This means, semantically, that these b-threads are never “satisfied” and must always advance. In the below diagram, b-threads 1, 2, and 3 form a group which has a hot run (states A→B→C→A…). If we only consider b-threads 1 and 2, on the other hand, there is no hot run, since none of them is hot at state C.

- Hot System Violation

- A case where the b-program, as a whole, might find itself in a cycle whose synchronization points are all hot. This is a private case of a hot run, where the considered group contains all the b-program’s b-threads. In the below diagram, the described system has a hot system violation, because of the cycle A→B→C→A.

- Hot B-Thread Violation

- A case where a single b-thread can get into a cycle were it is always hot. This is a private case of Hot Run, where the group that has the hot run contains a single thread. Normally, this situation indicates that some business requirement was violated, or that there might have been a programming error. In the below diagram, b-thread 5 has a hot b-thread violation, because of the cycle A→B→C→A.

- Hot Termination

- A case where a b-program terminates when one or more of its b-threads is hot. This is technically a safety violation, since the run is finite. However, these cases can be augmented to a Hot B-Thread violation, by adding a trivial self transition, from the terminal state to itself. In the below diagram, a run that ends at state X would be a hot termination violation. The dotted transition to and from state X is the augmentation to a hot b-thread violation.

A sample state graph of a b-program. This graph contains 5 states (A, B, C, X, Z). In each, there are five b-threads (1-5). At each state, hot b-threads are marked with a red background. This state graph contains various liveness violations, as described above.

Note

It is possible to select which inspections are preformed during verification. A DfsBProgramVerifier holds a set of inspectors, which can be added to by calling its addInspector methods. If no inspectors are added, a default set will be used.

From the Command Line¶

To verify a b-program from the commandline, simply add the --verify switch. Use --full-state-storage to force the verification to use the full state data when determining whether a state was visited (requires more memory). To concentrate on liveness violations, add the --liveness switch. To limit the (possibly infinite) depth of the scan, use --max-trace-length:

$ java -jar bpjs.jar --verify hello-possibly-broken-world.js

$ java -jar bpjs.jar --verify --full-state-storage hello-possibly-broken-world.js

$ java -jar bpjs.jar --verify --liveness --full-state-storage hello-possibly-broken-world.js

Assertions During Runtime¶

During normal execution (i.e. by a BProgramRunner), failed assertion cause program execution to terminate. The execution BProgramRunner’s listeners are notified of this failure. This approach is sometimes called “runtime verification”, and is useful to implement “emergency shutdown” mechanisms.

Note

- A more in-depth discussion of verification in BPjs, including some techniques, can be found in the BPjs paper at arXiv.

- Sample verification code can be found in the test code, in package

il.ac.bgu.cs.bp.bpjs.verification.examples.